Election Day

I voted this week—I won’t say how, that’s a matter of conscience—and voting is on my mind. It’s become fashionable to be cynical about voting. “Whoever you voted for, the government got in.”

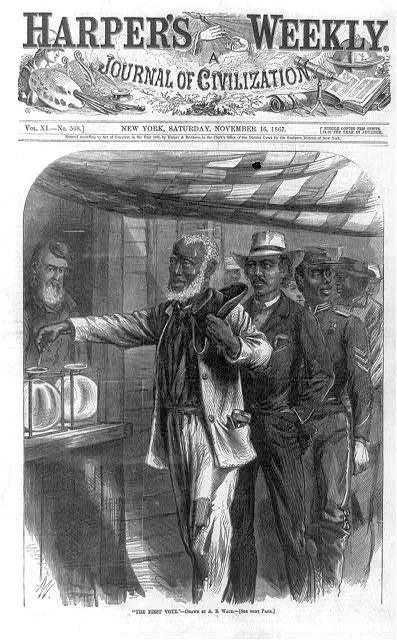

I’m writing a new novel about black folks in Mississippi in the mid-1880s, ten years after the end of Reconstruction and five years before the Jim Crow laws of 1890 effective disenfranchised Mississippi’s black voters. For these characters, voting was a highly significant act. It reminded them that they were free.

Politics mattered a lot in Mississippi after the Civil War. Black people were passionate supporters of the Republicans, the party of President Lincoln, which defended their freedom and their rights. Rallies and speeches were celebrations as well as events. Even though women didn’t have the franchise, they attended the rallies, listened to the speeches, formed their opinions, and lobbied the men in the lives, who went to the polls. Voting was a family business.

The South was full of black Union veterans, and they treated election day as an opportunity to remind themselves of the cause they had fought for—their own freedom. They put on their blue Union coats and polished the buttons so that the eagles gleaned bright. They marched down to the county courthouse, where the vote was held. And they walked in, holding their ballots high. They were proud to vote for the party of Lincoln, but they were pragmatists, too. They wanted everyone in the room to see how many Republican ballots went into the box. If their votes were stolen, they would know.

We’re used to secrecy in voting, but in the 19th century, voting was a highly public act. Each party printed distinctive ballots that would be obvious to an electorate that might not be able to read. In Mississippi, the Democrats had ballots printed bright yellow with a picture of a rooster, symbolizing the sunrise. The Republicans, the party of Lincoln, the party that carried the standard for black equality, printed ballots with the Union flag on one side and the American eagle on the other. Voters were advised to “vote the way you shot,” and even an illiterate farmer, a former slave, had no trouble figuring out which ballot to put in the box.

Starting with the 1868 elections, political campaigns and rallies in Mississippi were the occasion for racial violence. Black voters were intimidated during the campaigns, and they were obstructed from voting on election day. The lives of Republican candidates were threatened. In the worst instances, black voters were murdered, sometimes a few at a time, and sometimes in massacres that went on for days.

One of the proudest moments in a former slave’s life was the day he went to the county courthouse to register to vote. One of the most shameful moments in American history was the process in Southern state after Southern state that took the black vote away.

Image credit: Waud, Alfred R. (Alfred Rudolph). "The First Vote." Nov. 16, 1867, from Harper's Weekly.